Published by The National Observer on March 22, 2021

Last March, about two weeks into the pandemic, Steve Teekens got a call from the police. Teekens runs an Indigenous housing agency and the officers were calling to say one of his clients had tested positive for COVID-19. It was the first case to surface at the Native Men’s Residence, an organization that provides emergency shelter, transitional housing and deeply affordable rentals to a clientele of mostly Indigenous men in Toronto.

The client had been homeless and had recently stayed at the Na-Me-Res shelter. Teekens knew that could mean disaster. Inside the shelter, men share rooms and common areas and participate in programming — including Cree and Ojibwe language classes, drumming lessons and spirit circles — intended to heal and foster cultural pride. If one resident had the virus, it could spread quickly. In fact, when Teekens tracked down two men who’d shared a room with the infected client, one of them had the virus, too.

…

Canada’s National Housing Strategy, a 10-year, $55-billion plan launched in 2017, was supposed to help people like Quin. The Trudeau Liberals, however, have so far failed to develop a unified, Indigenous-led plan to address the housing needs of the 80 per cent of Indigenous people who live off-reserve.

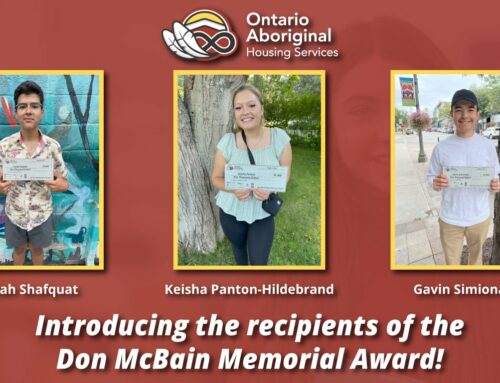

“At some point, the government needs to decide whether this is a priority or not,” says Justin Marchand, the executive director of Ontario Aboriginal Housing Services (OAHS), the largest of the province’s 38 Indigenous housing providers. “Because it keeps saying that it’s a priority and then not acting as if that were true.”

Marchand argues that a “for Indigenous, by Indigenous” housing strategy is integral to reconciliation. He says it would prevent more Indigenous children from entering the foster care system and help end a pattern of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls. “Housing is mentioned 299 times in the inquiry on MMIW,” he points out.